Fire Alarms

Photo by JOSEPH CEASmoke Detector

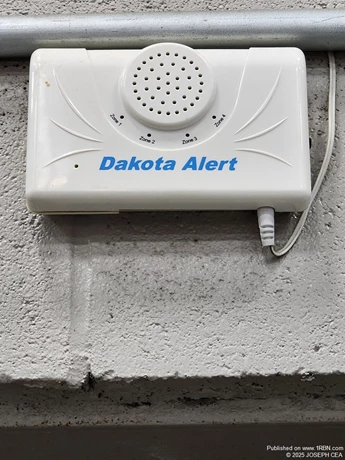

Photo by JOSEPH CEAZone CO detector

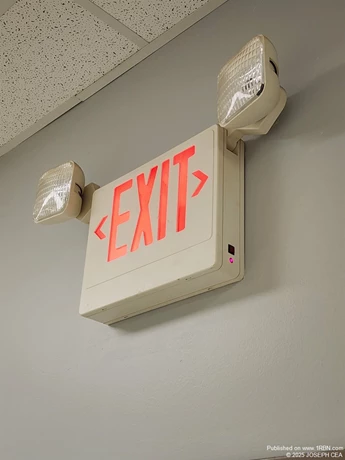

Photo by JOSEPH CEAEmergency Light with battery test button on the side - Copy

Photo by JOSEPH CEASprinkler head initiating device with temperature sensitive bulb

Photo by JOSEPH CEAaudio/visual warning device

Photo by JOSEPH CEAFire alarm control panel (facu)

Photo by JOSEPH CEATypical manual pull station

All fire departments have what is commonly referred to as “smells and bells” calls. The term refers to basic calls that may involve frequent flyers such as local restaurants. Firefighters may also use the term “routine” although arguably no call is routine; complacency being the subject for another day. Whatever these basic calls mean to your district one thing is certain and that is these calls will typically involve a fire alarm as the initiating device and the reason for boarding an apparatus.

Therefore, firefighters must have at least a rudimentary understanding of fire alarms and fire alarm systems. As with most required fire service knowledge and skills, instructors must first start with the basics and build up on how to apply that information. NFPA 72 and 25 govern fire alarm systems while 110 and 111 oversee the power supply.

To start each fire alarm system has to have a fire alarm control unit (FACU). This would be the brain of the system that monitors, controls and responds to disruptions. Obviously, the FACU is generally operating normally but there are three other conditions that can occur. The first is “alarm” which is an immediate threat to life, property and assignment. An alarm condition may be the result of a heat/smoke detector or a drop in water pressure. The second is a “trouble” condition which is in reference to an issue with the FACU itself as opposed to smoke condition such as a break in the circuitry. The last is a “supervisory” condition which indicates an issue with the system and/or any component parts. Supervisory mode can include other systems such as kitchen suppression or fire pumps because a FACU may control more than just fire alarms. An example of supervisory is when a FACU responds to a valve being stuck shut.

When a FACU has supervisory functionality, it may need to be temporarily shutdown in order to conduct any system testing. For example, weekly testing of a fire pump in accordance with NFPA 25 would require taking the FACU out of service while that test is being conducted. Also, most alarm systems have a test mode that allows it to function while testing or even construction is taking place. In the case of the latter, it is always wise to let an emergency dispatcher know the situation prior to notifying firefighters.

A fire alarm starts with initiation of device or circuit that signals the FACU into trouble or supervisory mode. There are multiple types of initiating devices such as fire, smoke, carbon monoxide, heat detectors (including rate of rise heat detectors), pressure devices and water flow devices. Also included are any manual devices such as a pull station. In a conventional system any of these devices will short circuit so that no other device in that “zone” can be activated thus leading firefighters to a general area. On the other hand, an addressable system sends a binary code (either a 0 or 1) that results in identifying a specific device.

This is an important aspect because when firefighters arrive at a location they want to quickly identify where a problem may be. Although it depends on the SOPs of the department firefighters should always advise residents or commercial managers to NOT reset an alarm system for this reason i.e. because it makes identifying an issue all that more cumbersome. Firefighters would rather search a specific zone or floor as opposed to an entire building.

Moving on to how alarm systems are powered? Obviously, there has to be not only a reliable primary source but also a reliable backup – we are talking about emergency situations after all. Typically, the primary power source is the local utility while backup sources are often an engine driven generator or acid/lead battery. Back up sources have to provide enough power for anywhere from 5-15 minutes in alarm and a full 24 hours in standby. This goes for not only the system as a whole but some components as well. Emergency lights for example generally have a button that when pressed indicate the battery backup is operating sufficiently.

Once a fire alarm signal is sent to the FACU how are occupants notified that the alarm is activated? That can be either by sound, voice or a visual cue. Visually, flashing lights are the most common but jurisdictional building codes (usually at the state level) determine the number, placement and type of notification device. Relative to sounds the volume level must be 15 decibels above average ambient sound and 5 decibels above the maximum sound. It is a good idea for firefighters and safety personnel to test fire alarms to make sure all occupants can hear/see the notification devices. One last note on notifiers is the type of sound. Temporal 3 is a three-tone sound (heard here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TfN5mpLdmys) that indicates evacuation is necessary whereas temporal 4 (heard here:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BziW_vCC-aA ) is a four-tone sound that indicates carbon monoxide.

The last part of alarm systems discussed here would be the monitoring of any FACU. NFPA 1221 standardizes the installation, maintenance and use of emergency services communications systems. In short this is all about who is monitoring any issues with the alarm system. This may be a public emergency system which is usually a municipality such as a police or fire station or even a private company. In both cases the on-site FACU acts as a transmitter that sends a signal that ends at the monitoring station which may be on site or operated remotely. In most cases both of these have 24-hour coverage which is obviously advantageous since the proper assistance can be dispatched to a given location.

To add to the definition of a monitoring station the term “proprietary” means it is owned by the same entity as the alarm property. College campuses are an example of this since most have a public safety building that is part of the campus property and staffed 24/7 to respond to any calls. Lastly, a central service station provides not only monitoring but also record keeping and periodic testing. It is therefore possible to be a proprietary and central depending on the functionality of the monitoring system.

Instructors must not only emphasize some of the alarm basics in accordance with the NFPA standards but also impress upon firefighters to familiarize themselves with their departments SOPs to make sure when arriving at a location due to an alarm drop that they can properly evaluate an alarm issue and put in place a solution. Here are some basic steps upon arrival:

1) Contact the property manager/owner and ask about when the alarm went off and if there is any construction or other activities that may cause an alarm to trip.

2) Find the FACU to silence and subsequently the zone and/or device in question.

3) Either reset the alarm or advise the property manager/owner to contact the alarm company used to reset the alarm.

One last note would be that firefighters would need to know enough about alarm systems to be able to identify a potentially dangerous situation presently and in the future. Although typically it is not in the prevue and training for firefighters to sanction a home or business owner it is their responsibility to call a municipal fire code compliance officer with reasonable suspicions of a violation.